Many runners would consider qualifying and running the Boston Marathon as ‘Holy Grail’ of running and one of the hardest things to do on their bucket list. Indeed, the atmosphere, the crowd support, everything about this World Major race is an amazing experience. However I firmly believe if an ordinary person like me can qualify, so can you.

Here are 10 things I did that helped me complete two Boston marathons and qualify every year since 2011. These tips are relevant to anyone who wants to do a good race, from those who have never run a marathon to those aiming for that Boston qualifying time.

1. Have patience

Getting fitter and faster to meet a race goal takes time, more so for runners who are less fit, or have less years of running experience. Here’s the good news about the Boston marathon – the longer you take, the older you will get, and the easier the qualifying time will be. It took me 3 years, from a decent 3 Hour 50 Minutes marathoner to patiently chip away 30 minutes to meet my age-qualifying goal of 3 Hour 20 Minutes. If you are under 45 years old, with dedication and proper training you can drop 30 minutes even faster.

2. Enjoy the process, because it takes years of dedication

Unless you like training, it would be very difficult to stay committed to a training regime. Pushing yourself beyond your limits is not necessary. ‘Train until you puke’ is so old school because that is the surest way to feel burnt out. Instead, for each training session, I set two goals – a challenging A-goal and an achievable B-goals. For me and my athletes, the challenge of trying to meet A-goals with the comfort being able to achieve B-goals is hugely motivating.

3. Find a coach, or follow a proper training program

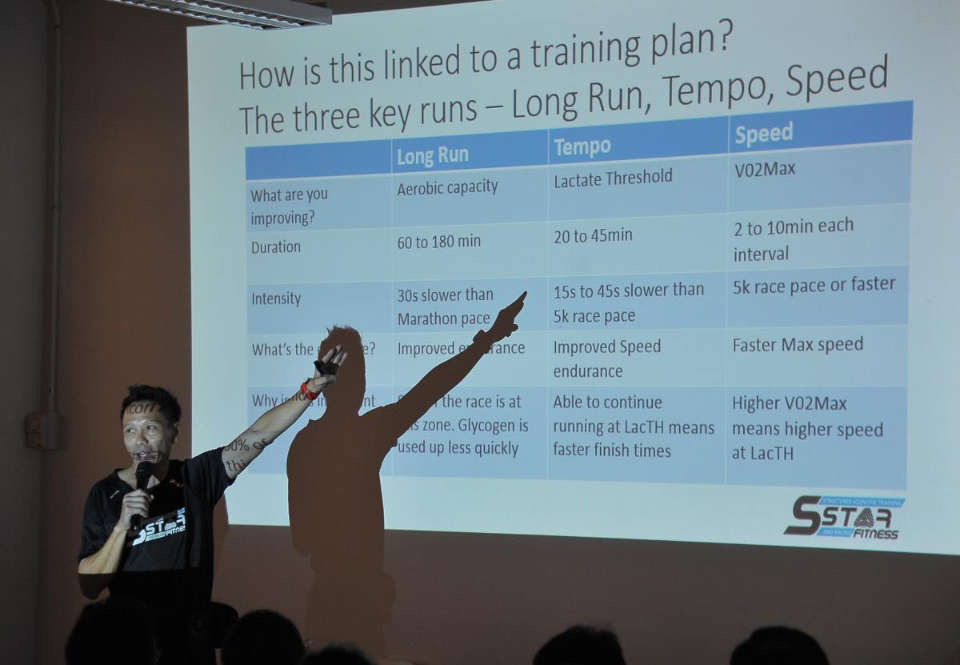

After years of running, I concluded that a random approach to training doesn’t work. As the saying goes, ‘’He (She) who fails to plan, plans to fail.’’ I had the privilege of meeting my mentors, Dr Bill Pierce and Dr Scott Murr, both Sports Science professors from the Furman University who developed the F.I.R.S.T training program. Their Run Less Run Faster training program was the breakthrough I needed. If you don’t want to waste time and effort, then invest in a good coach or at least follow a structured training program.

4. Experiment until you find what works

Every person is unique and no one training program is the best. You should have a uniquely tailored training program to achieve the best outcome. For example, I test my athletes to understand if they have more fast vs slow twitch muscles, if some running gaits are more efficient and tailor a training program based on their strengths.

In my quest for the Boston qualifier, I tried various training programs, from Galloway, Hanson, Pfitzinger to Higdon. None seemed to work until I tried Furman’s F.I.R.S.T Run Less Run Faster program. It matched my busy travelling work schedule, as I only ran three times a week, and that also helped me stay injury free for the last 7 years. I am such a convert that I now run a coaching program based on their training principles.

5. Be consistent

Success in endurance sport is all about consistent training. An analogy I often use when coaching – ‘’training for a race is like pouring water into a leaky bucket. To keep it full, you have to keep adding water. Overdo it and the bucket overflows.’’ So add water and train consistently to keep the water and fitness level high but don’t overtrain or add too much too soon. Personally I recommend to my athletes to have a ‘gap day’ between training sessions to rest or cross train. I qualified for Boston with three runs and relatively low mileage of less than 50km a week. Running six or more times a week is probably OK if you are very seasoned or at the elite level.

6. Stay injury free

Related to the earlier points, you can’t train consistently if you are injured, and a big cause of running injuries is overtraining. On my journey to Boston, I stayed injury free with cross training, daily core strength exercises (my training group now calls them Andrew’s 5BX) and also what I personally think works – Yoga and Pilates for runners. While flexibility is not essential for distance runners, some degree of it will help keep injuries away.

7. Choose the right race

Heat and humidity will affect all runners, as will extreme cold and rain. For ideal race outcomes, race in ideal conditions – 5 to 12 degrees C temp, low humidity, a flat, straight course with minimum crowd congestion. People have asked me ‘’you are a Singaporean, so why don’t you qualify for the Boston in Singapore?’’ Smiling to myself, I am glad I wasn’t born in the Sahara. I guess it would be an even greater achievement to qualify in tough local conditions, but I am no masochist, so I prefer to pick races where my chances of doing well are the highest.

8. Proper nutrition

Nutrition during training, pre-race and on race day itself is critical to success. I stuck to a conventional diet of 50% carbs, 25% fats and 25% protein throughout my training seasons. I ate real food, as natural as possible and limited refined sugar. I also ensured that I timed my nutrition correctly before and during the race. I would suggest avoiding fad diets that are not backed by sports science or not widely adopted.

9. Race smart and manage race day conditions

Run an even effort race. If you chose a flat course, that would be an even paced run. Both negative and positive splits tend to stress the body either too early or too late in the race. There is so much more to racing strategy beside good pace management – running tangents, how you approach the hydration points, bottlenecks, managing the mental aspect of the race, all these were things I had to be mindful of when I ran my Boston qualifiers.

10.Remember to rest

While we may know that rest is as important as training, not many actually follow a proper cycle of training and rest. When I was preparing for my races, I understood how and when I was building up mileage, or when to increase my intensity. I knew whether my progress was done at the right pace, and when I had to reduce training intensity to achieve the super-compensation effect. A coach with some sports science background should be able to help design training cycles to help you progress well.

There are runners that I know personally who don’t necessarily subscribe to some of these tips, but I am confident the majority do. As we are all unique, a different approach could work for them and I don’t profess to know what these are.

Perhaps exploring the myths and fallacies surrounding this seemingly simple sport of running could be a topic for another article in future.